BATIK

Resist-dyeing is an ancient process, but it flourished in Indonesia as batik (wax resist) where it became a much admired art form, highly prized by royalty.

Colonisation by the Dutch in 1800 led to the industrialisation of the hand-crafted process in an attempt to sell manufactured batik back to Indonesia. Selling ‘local’ fabrics to colonised markets was big business in Europe from the 18th century. Creating cloth for export could sustain huge companies in Britain or the Netherlands in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

In the renamed ‘Dutch East Indies,’ industrially-produced batik was seen as inferior to local products, leaving the Dutch in need of a new export market. There is some debate over how West Africa became this new market. It’s possible that Dutch ships loaded with batiks bound for Indonesia stopped at ports along the North West coast of Africa, leading to increased demand. Another theory is that soldiers from Africa stationed in Indonesia took batik cloth home with them which sparked interest. Whether through trade or war, the market for batik-style prints grew enormously, partly because indigenous resist-dye methods had been used as decorative techniques throughout West Africa for centuries.

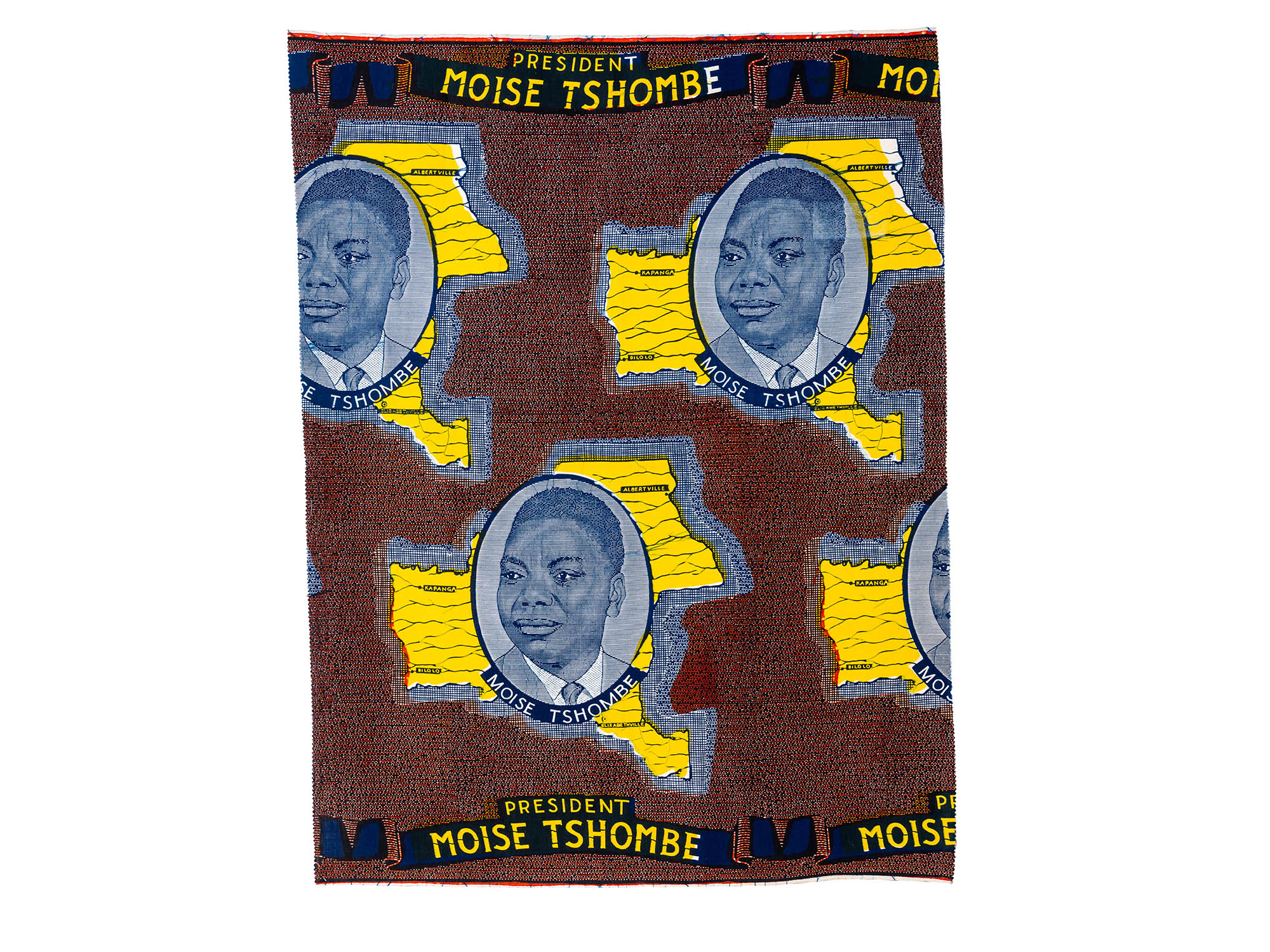

These textiles go under a number of names: Dutch wax print, Veritable Java print and ankara to name a few. Until the mid-20th century the majority of these prints were produced in Europe and sold to markets in Africa. European companies would take inspiration from indigenous prints and patterns in the market they were selling to. With the independence of many African countries in the 1960s, local manufacturing grew, whilst now these textiles are often manufactured in China.

Through pieces from the Gawthorpe Textile Collection in this corridor we can see the movement of the batik process from Indonesia to West Africa, via factories around Lancashire and Manchester.